"Cockney" means working-class from the East End of London, so I'd better say, not that he was the first proletarian leading man in Britain—other actors had changed their style of speech to accomplish that—but that he was the first to do it with his own accent.

"I'm every bourgeois nightmare—a Cockney with intelligence and a million dollars."

Before him the lower-class Englishman was a clown, a George Formby ("I'm leaning on a lamp-post at the corner of the street, In case a certain lih-o lady comes by...")—

—a Lonnie Donegan ("Oh, my old man's a dustman, He wears a dustman's 'at, 'E wears cor blimey trousers And he lives in a council flat..."), a Stanley Holloway, the Cockney of choice for Alfred Doolittle in My Fair Lady—

—and for Hamlet’s gravedigger, who, as in Shakespeare’s time, was a clown. Until Caine there was no other way to represent the British—well, with respect to Doolittle let’s not say working class—but the people, the many, the proles.

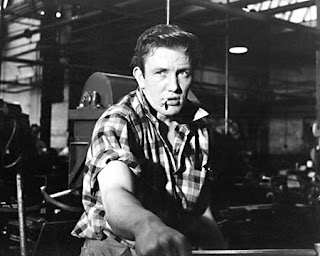

Yes, there had been Albert Finney in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (I still remember the gasp from the audience when he said “bastards”)—

—Tom Courtenay in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner—

— and Richard Harris doing his Brando imitation in This Sporting Life—

Caine himself broke in as an upper-class officer in Zulu in 1964—

—but in The Ipcress File the

next year, and in subsequent “Harry Palmer” movies, he was the insolent

Cockney connoisseur of classical music who annoys his snooty boss by

shopping in the same gourmet store. This was the kind of character I

could relate to even as a kid—someone who knew how to live! I’m still

writing books about that guy.

I wasn’t aware of this at the time, of course, but in the British imagination it was a revolution.

"The first actor I ever saw was The Lone Ranger. I thought, That's what I want to do."

What they have there is a caste system, because it’s more rigid than just class. In America (in the larger sense of that term; I’m Canadian) class is fluid. My father came from Highland clearance people (slaughter, prison ships, the whole nightmare—see My Racial Profile), who were dumped in Cape Breton, where they still speak Gaelic; peasants, but rich peasants; land-owners, but Catholics, with big families, ten kids to a generation dividing up the heritage. My great-grandfather worked wrought-iron as a hobby, and presented gates and grill work to his friends as gifts; my grandfather took it up out of necessity, and became a blacksmith; he taught my father, who was a hard-hat diver welding hulls in Halifax harbor; when he got to Toronto he found work as a mechanic in an abattoir. I, of course, am above money; like Toby in my novels I stay south of the Alps, where I can function at leisure, and not too often. You’re up, you’re down, you’re up again. But it ain’t that way in Merrie Olde England, kids.

I wasn’t aware of this at the time, of course, but in the British imagination it was a revolution.

"The first actor I ever saw was The Lone Ranger. I thought, That's what I want to do."

What they have there is a caste system, because it’s more rigid than just class. In America (in the larger sense of that term; I’m Canadian) class is fluid. My father came from Highland clearance people (slaughter, prison ships, the whole nightmare—see My Racial Profile), who were dumped in Cape Breton, where they still speak Gaelic; peasants, but rich peasants; land-owners, but Catholics, with big families, ten kids to a generation dividing up the heritage. My great-grandfather worked wrought-iron as a hobby, and presented gates and grill work to his friends as gifts; my grandfather took it up out of necessity, and became a blacksmith; he taught my father, who was a hard-hat diver welding hulls in Halifax harbor; when he got to Toronto he found work as a mechanic in an abattoir. I, of course, am above money; like Toby in my novels I stay south of the Alps, where I can function at leisure, and not too often. You’re up, you’re down, you’re up again. But it ain’t that way in Merrie Olde England, kids.

The British system has everything in common with Hindu caste. It cannot be married across. In Bombay newspapers (they say "Bombay" there, not "Mumbai"; that’s for politically correct Westerners) you'll see ads for marriage partners saying "Caste no object." That doesn’t mean a Brahmin can marry a non-Brahmin. A friend of mine in Goa who sold tee-shirts went to Madras to hire someone to dye them; the guy said, "I'll do the mixture for you but I can’t stir the pot; that’s against my caste. My partner here can do the stirring; you can hire us both for one salary." That’s what they mean by "Caste no object."

"Things are not quite what they seem always. Don't start me on class, otherwise you'll get a four-hour lecture."

And yes, the British and the Indians understood each other. I spent eight months in India, long enough almost to say I lived there, and it seems to me that the British broke India’s heart when, rather than bleeding down into the hierarchy like other conquerors, they simply peeled themselves off the top and left. They snubbed India. So like them.

You can’t marry across British caste either. Only in movies. Class differences can "spice" a marriage, Evelyn Waugh said, but just to a "Caste no object" degree. The traditional exceptions are heiresses—

—and footmen.

(For more on footmen see The Marquis de Sade, Father of Modern France.)

Try having a drink in a London pub after eleven: you’ll be out on your cleavage before the hour chimes. These people have to be in bed so they can get to the factory in the morning, and that’s the law. If you want to keep drinking you have to go to a "club" and mix with another sort. Members only.

(For more on footmen see The Marquis de Sade, Father of Modern France.)

Try having a drink in a London pub after eleven: you’ll be out on your cleavage before the hour chimes. These people have to be in bed so they can get to the factory in the morning, and that’s the law. If you want to keep drinking you have to go to a "club" and mix with another sort. Members only.

William Burroughs said, "We should be grateful to those Valley Forge boys for getting us out from under all that," implying that the American Revolution was about class. And that’s the way their allies in the French navy saw it: they went

back to France feeling that what the Americans had done, they could

do—and a few years later they did, in their way.

"In England I was a Cockney actor. In America, I was an actor."

It's a charming accent, much in style in the eighties and nineties with kids from other backgrounds. During World War II a Canadian airman was shot down over the Channel, woke in a ward full of wounded guys, passed out—and came to in a room by himself, which he found ominous; when the nurse came in he said, "Level with me, was I brought in here to die?" "Naaa-oh," she said, waving the thought away, "yew was brought in 'ere yestadie!"

It cannot escape notice that lower- and lower-middle-class British people ally themselves with, think of themselves as, think as, Americans. What’s the alternative? The revolution is just catching up with them. Cromwell’s was reabsorbed, and was never very tasty anyway (see Greece versus the Puritans).

"In England I was a Cockney actor. In America, I was an actor."

It's a charming accent, much in style in the eighties and nineties with kids from other backgrounds. During World War II a Canadian airman was shot down over the Channel, woke in a ward full of wounded guys, passed out—and came to in a room by himself, which he found ominous; when the nurse came in he said, "Level with me, was I brought in here to die?" "Naaa-oh," she said, waving the thought away, "yew was brought in 'ere yestadie!"

It cannot escape notice that lower- and lower-middle-class British people ally themselves with, think of themselves as, think as, Americans. What’s the alternative? The revolution is just catching up with them. Cromwell’s was reabsorbed, and was never very tasty anyway (see Greece versus the Puritans).

"Alfie was the first time I was above the title; the first time I became a star in America."

"Class is race," Nietszche tells us, and at the bottom of the British ladder you find Celts, people with names like Lennon and McCartney. In the middle you find Anglo-Saxons with names like Jagger and Richards. Notice how these men all made their fortunes affecting American accents (Mick shouting to the rioters at Altamont, "Y'all cool out, now!" Huh?) At least they think they’re Anglo-Saxons: now that doctors are looking at everyone’s genes they’re finding that most people who thought they were "English" are in fact Celts.

And on top are the Normans, from Norway via France. These days Norwegians are the butts of Scandinavian jokes (they can hardly tell blonde jokes, can they?), but in Gore Vidal’s phrase the Normans are still on their "high Norwegian horse."

That’s habit for you—and barbarism, too. To bow to someone wearing white fur and purple, to bow to someone wearing anything is barbaric. The Brits would have abolished it long ago if the Disneyland effect didn’t pull in so much of their GNP. The Revolution has not—not really—caught up.

So you can see why Maurice Micklewhite’s accent was so important to British, and even to American life. Sir Michael—for he has not rejected the honors due his achievement (would you?)—is the son of an Irish fish market worker, and he too gradually became American, though, superb actor that he is, he can do any accent. One of my favorite Caine portrayals is his Stalin in World War II: When Lions Roared. Even in his late seventies (this was written a while go) he’s one of the very few great stars.

"My career is going better now than when I was younger. It used to be that I'd get the girl but not the part. Now I get the part but not the girl."

I’d like to have had him for one of my own movies, and broached the subject with some associates. "Why does he get so much?" said one. "Because," said another, "he's Michael Caine."

On YouTube:

Boccaccio’s "The Husband"

Boccaccio's "The Horse Trade"

Boccaccio's "The Stupid Friar"

Chaucer’s "The Miller's Tale"