I don't want a state of grace; I want a state of gorgeousness!

In an age when beauty is out of style, the work ethic dominates the Internet and there hasn't been a painting or a poem for decades, let us reflect a little on gorgeousness.

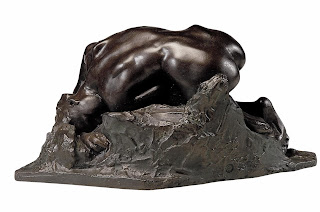

Seven Sculptures

The word is from the French for throat, so let Nefertiti be its patroness. This likeness is from five hundred years before Homer—who says the Greeks invented sculpture? Beautiful women, fully alive, have declined to be in the same room with her, so as not to suffer comparison.

Seven Seas

Homer, Scheherazade, Dante, Boccaccio, Rabelais, Montaigne, Shakespeare.

Seven Films

Trouble in Paradise, To Be or Not to Be (the Lubitsch version), Ninotchka, La Dolce Vita, 8 ½, Satiricon, Party (de Oliveira's).

Seven Novels

Seven Novels

Satyricon, Crime and Punishment, In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, The Great Gatsby ("there was something gorgeous about him"), Under the Volcano, Lolita.

Seven Beauties

Sophia; Audrey; Brigitte; Ann-Margret; Sylva; OK, Marilyn; and yes, Joan:

"Desire is always stronger than any virtue. Satan, ora pro nobis."—The Convent

"Trying to guess her weight?"—Baby catching Bogie with a woman in his arms in To Have and Have Not

Dean: “Where’s my drink?” Frank: “In your hand.” Dean: “Is that my hand?”—some Rat Pack movie

"And waiter, do you see that moon? I want to see that moon in the champagne."—Trouble in Paradise

All of them are from the P7 sixties—the post-penicillin, pregnancy-prevention-pill, post-puberty sixties, when sex was just being invented. Polymorphous perverse sex, I mean, and these women embodied it. In The Seven Year Itch Marilyn handles a heat wave by keeping her panties in the ice box.

Then came the aphrodisiac drugs (Blake predicted "an improvement of sensual enjoyment" around that time)—and scarcely a decade later, the new diseases. Now we don't have sex any more, not with other people, especially when we're married ("If you are afraid of loneliness," said Chekhov, "do not marry"), and have taught ourselves new desires, new ambitions, rather grotesque ones in my opinion. O Hamlet, what a falling-off was there!

Seven Ungorgeous Things

Music by Shostakovich; paintings by Jackson Pollock; German food (except for bratwurst); British food (except for fish 'n' chips); prose by Stephen King, Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney (I think they're all the same guy); California wine, unless nothing else is available—unless zero is available; milk.

Seven Paintings

Catholicism and Hinduism are gorgeous. Judaism, Islam, Protestantism—well. It seems you have to be polytheistic to be gorgeous. Being Catholic is a matter of infinite complications; being Protestant, of stark simplicities. The problem the Germans (pity them!) are having with the Greeks right now is one of infinite complications.

We've been surrounded by puritan imagery for two hundred years, Wordsworth's God brooding in solitude over the abyss. Homer's gods "dwell in bliss," and though that sterilizer Plato hates the idea, heaven may well be an orgy. Look at the company Michelangelo's God keeps:

Seven Movie Lines

"They call me Moose on accounta I'm large."—Murder, My Sweet

"Insult her. If she's a tramp, she'll get angry; if she's a lady, she'll smile."—Vivre sa vie

"Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don't know."—Camus's L’étranger, Visconti's film

"Insult her. If she's a tramp, she'll get angry; if she's a lady, she'll smile."—Vivre sa vie

"Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don't know."—Camus's L’étranger, Visconti's film

"Desire is always stronger than any virtue. Satan, ora pro nobis."—The Convent

"Trying to guess her weight?"—Baby catching Bogie with a woman in his arms in To Have and Have Not

Dean: “Where’s my drink?” Frank: “In your hand.” Dean: “Is that my hand?”—some Rat Pack movie

"And waiter, do you see that moon? I want to see that moon in the champagne."—Trouble in Paradise

Seven Musicals

The Smiling Lieutenant, 42nd Street, The Merry Widow, Gold Diggers of 1935, Pal Joey, Black Orpheus, My Fair Lady. Any musical choreographed by Busby Berkeley is bound to be rich in the subtlest and the most obscene pleasures. My own sense of tragedy, such as it is, comes from his Lullaby of Broadway. Like Mozart he is proof that the refined and the vulgar hold hands.

Seven Operas

"The three finest things God ever made are Hamlet, Don Giovanni and the sea."—Gustave Flaubert

"The three finest things God ever made are Hamlet, Don Giovanni and the sea."—Gustave Flaubert

The Barber of Seville, The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, The Magic Flute, La Traviata (by Cotrubas and Domingo, I beg you), Gianni Schicchi. OK, the Verdi and the Puccini suffer from post-Dickensian scmaltz. I've seen/read/heard the story of Camille so often that it seems safe; Don Giovanni is dangerous, as is Hamlet, as is the sea. Nevertheless, the music of Verdi and Puccini is undeniably gorgeous.

Opera is the Catholic art, the art of confession. "Do not speak to the driver," says a sign on an Italian bus, "he has to keep his hands on the wheel." What, I have wondered elsewhere, would Protestant opera sound like? It would sound like Wagner, the end of melody, the end of pleasure.

The nordic Protestant Richard Wagner killed opera dead. Moralism, sentimantality (the two are the same: Wagner wrote Here Comes the Bride), Christianity, gnosticism, all kinds of puritanism, and to go with them, atonal music. Verdi the sentimentalist fell in love with Wagner the moralist, and that finished it. Check Philip Glass for the current state of the art. In The President's Palm Reader a hostess asks Word what he thinks of the New Music: "It's great!" he says; "You can hum a tune while you're listening to it!"

All thought aspires to the condition of aria. Imagine allowing your soul to sing—to sing your sins to your confessor, your worries to your psychiatrist, your passion to your lover, your despair—the greatest of human pleasures—to whoever. But no, despair is denied us; there are always other tables to bet at; the universe, as Tennessee Williams said, is a great big gambling casino.

Seven Drawings

Opera is not amoral, it is quite deliberately immoral, in the Christian sense: it is pagan. The Bonn-born Beethoven was shocked when he first heard Così fan tutte ("You can live without love, but not without lovers"), and wrote the unsingable and, for those with my pain threshold, the unhearable Fidelio.

The Magnificent Seven

Louis, Cole, Django, Stéphane, Henry, Nino, Miles. After Wagner flushed melody it was up to Louis and Cole to fish it out and get it dancing again. Louis Armstrong is gorgeousness, the gorgeousest of all musicians, a poet with three voices—his composer's voice, his unmistakable flat-out in-your-face trumpet, and his voice voice which, with Domingo's, is the best male one we have. He taught Ella; he taught Frank; he created American music. Emerson put Shakespeare down because he was a mere entertainer, but entertainment is everything.

Miles Davis, after departing the Kind of Blue mode ("I have no feel for it anymore—it's more like warmed-over turkey") was Wagner's grandchild. Bitches Brew doesn't resolve musically, so it doesn't live in your memory; you recall only a phantasmagorical present. It's the closest thing there is to illegal music. But as with Beethoven and Nabokov, I feel with Davis that I'm in the presence of a bully—and yet not with Hemingway!

Seven Westerns

I hate Westerns! Except sometimes: Stagecoach, Shane, The Professionals, The Good the Bad and the Ugly, The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue, The Outlaw Josey Wales. Ford's hypnotic framing is always wasted on the most pedestrian subjects. The Professionals is the best of them all: "You bastard!" "Yes, sir, by an accident of birth. But you, you're a self-made man."

The Wild Bunch owes it everything, but one must admire those god-men who so bestride the world. Of course I have no interest in machismo—I can barely get the plug out of the hot-water bottle—and when Peckinpah eases up on it, as in The Ballad of Cable Hogue, he makes real poetry. Eastwood I contemplated in the Lubitsch piece.

Leone is the most shamelessly intellectual of them. He must have been shocked at the popularity of that work of semiotics and film criticism, A Fistful of Dollars. It founded an entire genre. His title The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a gloss on Wittgenstein's "Ethics and aesthetics are one," but the meat is a historical analysis of the industrial revolution and the Western's time in history: the cowboy and the gunfighter thrive between the Civil War and the arrival of the steam engine, and that train is always being built in his movies. Witness the scene where Eli Wallach assembles his pistol out of interchangeable parts. Heavy stuff, and off-putting if you're not hip to his mid-century out-Godard-Godard sensibility.

Which reminds me:

Seven More Movies

Pickup on South Street, The Seven Samurai, Contempt, Death in Venice, Happy New Year, The Night Porter, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. In the sixties Lelouch's A Man and a Woman was the movie of romance; now it's embarrassing to watch. His gem is Happy New Year, a beautifully controlled romantic heist, worth it alone for the pre-Steadicam hand-held one-shot scene in which Lino Ventura, fresh out of jail, cases his mistress's place and slips out when her new boyfriend arrives.

"All our final decisions are made in a state of mind that is not going to last."—Marcel Proust

"It’s not true that a woman can change a man. I don't want to tell another lie."—8½

"It would be better if nothing existed."—Mephistopheles in Goethe's Faust

"Even damnation is poisoned with rainbows."—Leonard Cohen

We sink in the sweet quicksand of Shakespeare. Perhaps the secret of his haunting voice is the despair in it, the dying fall, the tragic joy. One must look hard to find a triumphant character in him; perhaps only Rosalind sweeps the board. (Do yourself a favor and see the Elizabeth Bergner version.) He teaches us how to be no one.

Which reminds me—

Seven Desperadoes

"The beautiful is that which fills us with despair."—Paul Valéry"All our final decisions are made in a state of mind that is not going to last."—Marcel Proust

"It’s not true that a woman can change a man. I don't want to tell another lie."—8½

"It would be better if nothing existed."—Mephistopheles in Goethe's Faust

"Even damnation is poisoned with rainbows."—Leonard Cohen

We sink in the sweet quicksand of Shakespeare. Perhaps the secret of his haunting voice is the despair in it, the dying fall, the tragic joy. One must look hard to find a triumphant character in him; perhaps only Rosalind sweeps the board. (Do yourself a favor and see the Elizabeth Bergner version.) He teaches us how to be no one.

"Devotion is a kind of despair, and only in despair can we find happiness, which is why I will not deprive myself of my abandonment by the man I love."—Agustina Bessa-Luís, Party

Tragic, comic, who cares; what matters is gorgeousness. I said that there have been no poems recently, but Portuguese Agustina Bessa-Luís, who scripted the best de Oliveira's films, Party and The Convent, does the real thing. Alas, I am unable to find translations of her books and am confined to subtitles in her movies, which are of an aristocratic gorgeousness alien to what one of her characters calls "the democracies."

Tragic, comic, who cares; what matters is gorgeousness. I said that there have been no poems recently, but Portuguese Agustina Bessa-Luís, who scripted the best de Oliveira's films, Party and The Convent, does the real thing. Alas, I am unable to find translations of her books and am confined to subtitles in her movies, which are of an aristocratic gorgeousness alien to what one of her characters calls "the democracies."

Which reminds me—

A Further Seven Films

The Pink Panther (the original), Charade, How to Steal a Million (such exuberance!), Some Like It Hot, Toby Dammit, La jetée, The Convent. I've seen The Convent two dozen times—but don't go in there expecting a movie movie. These people don't give a damn about what we expect. Ah, to be financed like that!

Pop Music?

No. Too gospel-derived. Repent! Atone! The day of judgment is nigh! "And one of these days, baby, and it won't be long, you gonna come back crawlin on yo knees, and you gone be sayin, I still love you! Always thinkin of you! I still love, love, love—" Get lost. It gives rise to the uneasy spectacle of Presbyterians dancing. Gorgeousness is not a judgement, it's an appetite.

Elvis, yes—no brains, but a genius, and a gorgeous one. Johnny Cash, OK, I can't say no to the lyric poet of the American South. "When I was just a baby, my mama told me, Son, Always be a good boy, don't ever play with guns. I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die. When I hear that whistle blowing, I hang my head and cry." If shooting a man to watch him die doesn't do it to you, what that sight has to do with the sound of a train whistle—Pow. Wham. Gotcha.

Seven Fools

Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel, Hardy, Alberto Sordi, Lucy, Jackie Gleason. If I were listing actors Gleason would be at the top, with Mickey Rooney, James Mason—I can't think who else now. Michel Piccoli.

A fool is without dignity. A fool sees through dignity. A fool has no use for dignity, except to puncture it. Especially his own.

If you make a fool of yourself deliberately, it’s a triumph. If you make a fool of yourself and it’s not deliberate, it’s humiliating. If it’s deliberate but people think it’s not deliberate, it’s still humiliating—so important is the opinion of others—to me, anyway, but then I’m a fool. The great fools brave this double edge and go all the way into being fools. They live without approval. Not easy.

It's like being ugly. It is being ugly. At the end of City Lights the blind flower girl, her sight restored, looks up at the hero who has done this for her and sees—Charlie. Ooh, bad moment.

Do I see myself as a fool? Only of the undeliberate kind. To be a fool is a holy calling.

Seven Desserts

If you make a fool of yourself deliberately, it’s a triumph. If you make a fool of yourself and it’s not deliberate, it’s humiliating. If it’s deliberate but people think it’s not deliberate, it’s still humiliating—so important is the opinion of others—to me, anyway, but then I’m a fool. The great fools brave this double edge and go all the way into being fools. They live without approval. Not easy.

It's like being ugly. It is being ugly. At the end of City Lights the blind flower girl, her sight restored, looks up at the hero who has done this for her and sees—Charlie. Ooh, bad moment.

Seven Desserts

Crêpe Suzette, zabaglione, mousse au chocolat, strawberry cheesecake, bananas in white wine, fudge cake, Tia Maria on vanilla ice cream. Each of these is in its own way a dehumanizing experience, like good sex, and should be preceded by foie gras with Sauternes, and then lobster and champagne (champagne goes with any sea food, I find), followed by a Bûcheron chèvre with Pouilly-Fumé. Or substitute for the lobster a filet de bœuf served raw and in pieces to be grilled on your own heated iron—I love it when they give you those—with a red Bordeaux. And try to control yourself.

Toby's Seven Favorite Pleasures

My alter-ego, lazy worthless Toby Tucker, hero of my comic novels, has, for preference, these:

I lay there, nudged by the lightest possible stirrings of current, waving like seaweed. Here, I congratulated myself, I could combine two of the pleasures afforded by the mortal coil: sleep and immersion in a liquid. Ingestion, elimination, gossiping, shopping for shoes, driving around listening to The Doors and making uh-uh would, for the moment, just have to wait.

Which is eight, actually, not seven. But that's Toby.

I lay there, nudged by the lightest possible stirrings of current, waving like seaweed. Here, I congratulated myself, I could combine two of the pleasures afforded by the mortal coil: sleep and immersion in a liquid. Ingestion, elimination, gossiping, shopping for shoes, driving around listening to The Doors and making uh-uh would, for the moment, just have to wait.

Which is eight, actually, not seven. But that's Toby.

PS: Roman Tsivkin, a man of deeper culture than my own, was gracious enough to praise this piece, even while correcting me on Shostakovich, whose work I list among things ungorgeous. ‘If anything,’ says Roman, ‘his music should have the designation "ugly beauty"’ [pretty much what I feel about the above Rouault painting of the prostitute]. He sent me to hear Shostakovich's Cello Concerto No. 1, which has all the Russian passion you could ask for (there’s nice camera work in the film on YouTube), his 7th Symphony and his jazz waltzes. And I have learned a new pleasure, for which I’m grateful.

.jpg)

_06.jpg)